このページは品川心療内科「品川心療内科ブログ保存庫A(OCN,goo)」です。(236個)

「リンク切れ」多発

最近になって見てみたら「リンク切れ」があるようです。

リンク先はもう存在しないので見ることはできません。

そのうち少しずつ整理するつもりです。

社会不安障害(SAD :social anxiety disorder)について

社会不安障害(SAD :social anxiety disorder)について

最近は社会不安障害の用語を耳にすることも多くなった。従来日本では「対人恐怖症」または「対人恐怖」とよんでいた病態が近く、しかもそれは社会不安障害よりも広い概念である。海外でもtaijinkyoufuとして確定された概念と認識されている。

SAD :social anxiety disorder の翻訳語は社会不安障害として確定されている。社会はsocialの直接の翻訳語であるが、対人関係とか、人付き合いとか、もっとはっきり言えば「他人」が問題である。

概ねを言えば、社会不安障害では「他人に見られること」や「他人に判断されること」に過度の不安がある。自分の行動が「他人から否定的に評価されることを常に恐れて」いる。対人緊張が高まると、震え、赤面、動悸、悪心などの身体症状が生じる。しかしここまでならば単に対人緊張の強いシャイな人である。ここから回避行動が生じ、予期不安が見られる場合、SDAと診断されることになる。回避行動とは、行くべきところに行けないこと。たとえば会議に出席できない。好きなコンサートに行けない。学校に行けないなどである。予期不安は、不安な場面を頭の中でリハーサルして何度も不安を体験してしまうことである。SADと診断する際には社会活動に制限が生じることが目安になる。また、彼らは自分の不安を不合理であると明確に自覚している。それなのに不安を止められないと悩んでいるのである。「不合理の自覚」は強迫性障害診断においても大切とされている点なのであるが、確認は容易ではない場合もある。

SADの人がどうしても人前に出なければならない時、アルコールの助けを借りることがよくある。そしてそれが常習的になることもよくある。従って、アルコール症の背後にSADがないかどうか、吟味する必要がある。

SADにも重症度の違いがあり、不安の場面がかなり限定されている場合は軽症、場面が増えてあらゆる場面で不安が見られるようになると重症タイプになる。

最近では障害有病率は5~10%程度といわれている。決して少なくない。女性の方が多いと言われている。この内容については子細に検討が必要と思われる。また20歳代より前の若年層に多いと観察されており、30~40歳を過ぎて初発するケースは稀と言われる。社交技術(social skill)が発達するからだろう。診察室では、中学から大学にかけて、学校場面での困難に直面する例が多い。最近の学生は内心を言語化する能力が低いので、診察には苦労することが多い。

SAD患者は未婚者が多く、長じても25%は結婚の経験がない。結婚したとしても、離婚することも多い。親戚づきあいが出来なかったり、家族ぐるみの交流ができないからだと言われている。

SADと診断された人で、他の病気を同時に診断される人が50%もいる。多いのはうつ病であり、SADの20%はうつ病と言われる。これは社会生活に制限が生じ、同時に家庭生活にも制限が生じるので二次性にうつ病になったと考えることも出来るし、もともと原発性にうつ病の人が、人づきあいの面で制限を感じて、結果として社会不安障害と診断される面もあると思う。アルコール症は当然多く、自殺未遂も多い印象がある。

病気としてのSADと「内気な性格」、あるいは「回避性人格障害」の鑑別は困難な問題になる。ポイントは社会生活に制限支障が出ればSADと言うべきであることである。本人または家族が実際の不利益を被れば、SADと診断して治療を開始すべきだと思う。また、スキゾタイパル人格障害、スキゾイド人格障害、パニック障害との鑑別も必要である。パニック障害の場合には一人でいる方が不安が高まり、誰かと一緒にいたがる。一方、SADの場合には、他者と一緒にいることが苦痛である。

治療はまずSAD単独の病態なのか、うつ病やアルコール症をも併発している病態であるかを鑑別診断する。併発病があれば当然治療すべきである。併発率が最も高いのはうつ病であり、かつ、SADそのものについてもSSRIが有効であるから、これが第一選択薬になる。フルボキサミン(商品名ルボックス)を最初50mg、徐々に増量して3週後に150mg、その後経過を見て150mgを維持量とするか、300mgまで増量して維持量とする。副作用は口渇と便秘程度で、重篤なものはない。奇異な反応があったら注視して観察する。

効果発現まで2週から4週が目安になるが、データからは3ヶ月を経過してからでないと、効果の有無を結論できない。ここで注意したいのは、3ヶ月の後に無効であったとして、無駄なのかと言えば、そうではないことである。併発しているうつ病うつ状態については改善が見られていることが多い。結論としては、最適維持量を最低3ヶ月は継続すべきである。

指摘されている事実として、薬剤開始1週目で不安が強くなる場合がある。これはSADだけではなく、GADの場合にも、フルボキサミンで見られる現象である。しかし、その後不安が低下して、次に回避行動が低下するので安心していい。実際にはLSASという社会不安尺度で測定して論じている。この1週目の不安の増大に対してはベンゾジアゼピン系抗不安薬(たとえばソラナックス、ワイパックス、メイラックス)を用いて、不安を抑える戦略がよいだろう。この際にクロナゼパム(ランドセン、リボトリール)も勧められるが、日本ではてんかんの病名がなければ使用できない。

フルボキサミンの他に日本ではパロキセチン(パキシル)を使用することができる。初回20mgで開始して、40~60mgまで増量し、3ヶ月維持する。そこで効果を評価する。

ルボックスやパキシルで3ヶ月を経過して、その後維持し、最低一年は継続する。その後に薬剤を減量して症状再発のない場合には治癒となる。症状再発した場合には同一薬剤を継続する。長期投薬を要する場合の例をあげると、うつ病を併発している場合、社会不安障害発症が人生早期であった場合、回避性人格障害を併発している場合、薬剤コンプライアンスが悪い場合(つまり薬を飲んだり飲まなかったり不安定な場合)、遺伝性のある場合、再発を反復している場合などがあげられる。

SADは有病率が高く、未治療で放置した場合、うつ病やアルコール症を併発する場合が多く、その点でも積極的に治療する意義が高い。薬物療法を1年以上継続した場合に社会生活制限から開放されることが多い。ある程度時間がかかるのは、社交において自信がつくまで時間がかかることも理由である。

結論として、ルボックスを150mg一年飲んでみよう。人生が広がる。

2005-10-8不安症状の評価スケール

1.Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-Ⅳ(ADIS-Ⅳ) (IS)

これは,DSM-Ⅳの診断基準に基づいた不安障害の半構成化面接基準(IS)である。これに従えば,個々の不安障害の診断と除外診断ができる。

2.MAS;Taylor Scale or Manifest Anxiety

ミネソタ多面人格目録MMPI(Mennesota Multiphasic Personal Inventory)11)を基礎にして発展したスケールである。TaylorはMMPIの中から不安に関係する情動的・認知的・身体的反応項目を抽出して,個人の比較的安定している不安傾向を測定することを目的とした。この点,STAIのTrait-Formと類似している。本来,刺激に反応する際の個人差要因としての不安を測定することを目的として開発されたが,その後精神医学や心身医学の領域での不安測定によく用いられるようになった。現在市販されているのは,65項目,3件法の尺度である。{日本語版MMPI MAS:発行株式会社三京房 京都市東山区今熊野ナギノ森町,電話075-561-0071}

3.一般健康調査質問紙(GHQ);General Health Questionnaire

GHQは140項目からなる4段階評定尺度であり,全身の症状(17項目),局所的身体症状(18項目),睡眠と覚醒(19項目),日常的行動(22項目),対人行動(20項目),日常生活での不安やトラブル(25項目),抑うつ・不安(19項目)の7つの下位尺度が含まれている。GHQの目的は精神障害のスクリーニングであり,最近,症状の簡単なスクリーニングのために,28項目版といった短縮版が用意されている。{日本版GHQ28:発行 株式会社日本文化科学社 東京都文京区本駒込6-15,電話03-3946-3131}

4.POMS;Profile of Mood States(POMS,気分調査表)(Q)

McNairら(1971)によって開発され,過去1週間の「気分の状態」について測定するものである。POMSは,個人のおかれた条件の下で変化する一時的な気分・感情の状悪を測定することができ,6つの下位尺度,すなわち,緊張と不安,抑うつと落胆,怒りと敵意,活力と積極性,疲労と無気力,混乱と当惑から構成され,全部で65質問項目があり,5件法によって評定を求める。McNairらによれば,POMSは精神科の外来患者の状態把握に極めて有効であるほか,種々の治療法に対する反応を知る際にも非常に敏感な指標となり得る。また,健常被験者や非精神科領域の集団に対して,種々の実験的研究の効果判定にも信頼性の高い尺度である。

5.STAI;STATE-TRAIT ANXIETY INVENTORY

Spielbergerの状態 - 特性不安理論(state-trait anxiety theory)に基づいて作成され,状態不安を測定するState-Formと特性不安を測定するTrait-Formの2つに分けられる。状態不安は脅威的状況におかれたときに喚起される一過性の不安状態を指し,特性不安は個人の性格特性としての不安状態を指している。STAIのState-Formは横断的調査研究や実験的研究における不安状態の主観的評定に用いられることが多く,20項目からなる4段階評定の尺度である。わが国においても,日本版標準化の試みがなされ,これまで,遠山ら33),岸本ら14),中里ら19)による日本語版STAI,清水ら28)による大学生用日本語版,大村21)による日本大学版ⅡSEQ-STAIなどがある。

Ⅱ.ハミルトン不安尺度(HAS)

ハミルトン不安尺度はHamilton10)によって作成され,不安神経症と診断された患者の不安状態を測定することを目的としている。本尺度は不安神経症の症状の量を測定することに焦点をあて,測定内容は不安の精神的経験,筋肉や内臓の症状,抑うつ気分,不眠,インタビューの際の認知的障害といったさまざまな領域に及び,高い信頼性を有している。また,本尺度が作成された当初,不安神経症のさまざまな症状がグループ化され,13の変数に基づいた因子分析の結果,不安に関する1つの総合的因子,あるいは「精神的」および「身体的」といった2つの因子によって尺度が構成されることが示唆されている。本尺度はアセスメントを行う際には,2人以上の医師で用いられ,5件法で行われる。

Ⅲ.Clinical Anxiety Scale(CAS:臨床不安尺度)

Clinical Anxiety Scale(CAS)はSnaithら29)によってHASの改訂版として開発されたものである。本尺度は,HASに含まれる抑うつや不眠症などの症状を測定する項目を取り除き,主に臨床患者の現在の不安状態に焦点をあて,不安神経症より神経症性の障害,および不安人格障害の測定に有効であると指摘されている。本尺度はSnaith らによって項目分析が行われ,信頼性の高い6項目(精神的緊張・筋緊張・刺激反応・心配・不安・落ちつかなさ)から構成され,5件法によって回答が求められる。

Ⅳ.Zung 自己評価不安尺度

Self-rating scale for anxiety(SAS)はZung35)によって作成された不安障害の評価尺度である。本尺度が作成された当初の目的は,精神障害とみなされる不安を評定および記録する標準的な方法を開発することであった。本尺度は以下の基準,すなわち,精神障害とする不安障害の症状を含めること・症状を量的に測定できること・短くて簡便であること・2つのフォーマット(患者が自己評価尺度によって自分の反応を説明するものと観察者は同一の基準に基づいて臨床的評定を行えるもの)を含めることに基づいて作成されたものである。本尺度は精神障害とみなされる不安の基本的症状(5つの感情症状と15の身体症状)を含め,患者は20項目についてこの1週間の状態を4件法で回答が求められている。

Ⅴ.シーハン不安尺度 Sheehan Patient Rated Anxiety Scale(Q) http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t1.htm

これは不安症状を同定してその重症度を5段階に自己評定する尺度である。筆者らのクリニックでこの日本語版を作製し,162名のパニック障害患者の回答を分析した17)。その結果シーハン不安尺度は不安症状という1つの主成分構造を持つ尺度でその内的統合性(α=0.95)は十分で,種々のパニック障害の症状との相関性が高く ,パニック障害の重症度を測定する尺度として妥当性を有していることが明らかになった。パニック障害患者162名の得点分布は のごとくである。初診後2年半以上経過した予後調査において,この不安尺度の回答が得られた84名の患者についてみると,評点は40.1点から17.5点に減少していた 。日本語版の標準化はなされていないが,原著によれば,30点以上が異常,80点以上が重症,パニック障害患者の平均得点は57±20点であり,治療目標は20点以下に下げることである。

Ⅵ.パニック発作・恐柿症

1.MINI(IS) http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t3.htm http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t4.htm

MINIは,短時間に簡単に診断できる構造化面接手順である。パラメディカルスタッフも簡単な訓練で使用できるよう工夫されている。現在世界の43カ国語に翻訳されており,今後世界中で幅広く使用されることが予想される。MINIは17種類の精神障害を約19分で判定する。MINI plusではもう少し詳しく問診でき,33種類の精神障害に対応できる。小児用にはMINI kidがある。MINI trackingは各質問に「ない」「経度」「中等度」「高度」「非常に高度」の5段階の評点をするようになっており,重症度を知ることができる。 にMINIのパニック障害の項を示す。

2.Panic Attack Questionnaire(Q)

パニック発作の誘発因子,頻度,程度を患者が週に1回自己記入する簡単な質問表である。パニツク発作の程度は目盛りで視覚的に示すよう作られている[Patient-rated visual Analog Scale (VAS)]。この質問表はアルプラゾラムやイミプラミンのパニック発作に対する効果の検定に利用された。

Panic Diary(Q)はパニック障害の治療薬の検定に際してよく使用される方法である。Ballengerら1)はアルプラゾラムの治験に際してTaylorら32)の方式を採用した。彼らの使用した日記の中でみられるパニック発作の記載は,6日間のホルダー心電図検査で異常が出たときとよく一致した。患者は日記にすべての発作と予期不安エピソードを記載するように要請された。どの発作でもエピソードでも,その程度(1~10),パニック発作症状の種類,持続時間,その間何をしていたかを記載することになっていた。さらに患者は,特発性の大発作(1型),小発作(2型),予期不安エピソード(3型),状況性パニック発作(4型)に区別するよう指示される。最近のSSRIの治験研究3,18)にはSheehan Panic Attack Diary26)が使用している。これは,パニック発作が起きた日時,場所,および発作症状が日記に記される。さらに,発作の強さを0~10点で評点する。

3.Panic and Agoraphobia Scale パニック障害・広場恐怖症評価尺度(Q,RS) http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t6.htm http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t7.htm

このスケールはDSM-Ⅲ-R/ⅣまたはICD-10で診断がなされた後,パニック障害の重症度を測定するために作製された。患者が自己評点する版 でも医師が評点する版 でもClinical Global Impression のそれぞれ自己評点および医師評点と相関性が高い。質問項目は,パニック発作,恐怖性回避,予期不安,人間関係および職業上の障害,身体疾患へのとらわれの5つの要素に分かれており,薬物治験に利用できるように考慮されている。

4.Panic Disorder Severity Scale(RS)

1)パニック発作の頻度,2)発作中の不快度,3)予期不安(未来のパニック発作を気にする),4)広場恐怖と回避,5)内受容器感覚性の恐怖と回避(温度や湿度が高い,運動で心悸昂進を招く,映画で興奮する,プレゼンテーションをするなど),6)職業上の障害,7)社会生活上の障害の項目からなり,パニック障害の診断がDSMなどで確立した後にその重症度を検討するために使用される。まだ,使用数が少なくその有用性の有無は将来の問題である。

5.Panic Questionnaire(Q)

パニック障害の診断が確定した,または疑いのある患者に対してパニック障害の特徴を広範に量的に調査可能なスケールである。

6.Albany Panic and Phobia Questionnaire(Q)

前述のスケールを作るのに参考になった質問表である。広場恐怖以外に,身体の不快感(発汗,心悸昂進,便意など)を引き起こすような状況に対しての恐怖と回避をも調べた点がユニークである。32項目の因子分析から広場恐怖,社会恐怖および内受容器感覚性の恐怖の3つの要素が区別された。この評価尺度はパニック障害の実地臨床でも研究でも利用することができると作成者は述べている。

7.Fear Questionnaire(Q)16)

恐怖・回避対象を検査する質問表である。3つの部分から構成される。まず,患者が最も恐れる対象を患者自身の言葉で書かせ,次に広場恐怖,血液・外傷恐怖,社会恐怖に関する恐怖対象となる事物や状況をそれぞれ5つあげ ,さらに,それ以外の恐怖対象を具体的に書かせ,それらすべてに全く回避しない(0点)から常に回避する(8点)まで8段階評価をさせる。最後に,不安と抑うつの程度を測定する5項目の質問に対して,さらに具体的な悩みを書かせ,それら6項目に対して,ほとんどない(0点)から非常に強く悩む(8点)まで評点させる。

8.Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia(Q) http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t8.htm

これは自己記入式の回避行動検査法である。Fear Questionnaireよりも詳細で,26項目からなる状況に対して,1人だけの場合と付き添いがいる場合に分けて回避行動の程度を評価することができる。また,過去1週間のパニック発作の頻度も評価できる。広場恐怖患者とその他の不安障害の患者との判別が可能な信頼性の高い検査法である。この質問表は,個々の患者にあわせた暴露療法のプログラムを作るのに有用である。また,薬物療法がなされていない重症患者を検討する改訂版も出ている。それにより,患者が薬物に強く依存している状況も調べることができる。

9.Brief Social Phobia Scale簡易社会恐怖評価尺度(RS) http://www.fuanclinic.com/ronbun/r_14t9.htm

社会恐怖の観察者が評価するスケールである。7つの状況 について恐怖の程度と回避の頻度を調べ,さらに赤面,動悸,震え,発汗という4つの身体的反応の程度をそれぞれ5段階評価する。主に薬物の治験に利用されている。

10.リーボビッツの社会恐怖評価尺度(R8)

これも観察者が評点する社会恐怖の評価尺度である。恐怖の対象となるパフォーマンス状況および社交状況がそれぞれ12項目あり,それに対して恐怖の程度と回避の頻度をそれぞれ4段階評価する。

11.Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale

日本版FNE 尺度(Q)

FNEは他者からの否定的評価に対する不安を自己評価する尺度である。FNEは社会恐怖患者の臨床的特長をよく示しており,社会恐怖の治療研究においてこの得点の変化が社会恐怖の改善を予測する。採点は,「はい」を1点,「いいえ」を0点として合計点を算出する。13項目は逆転項目であり,「いいえ」を1点として計算する。筆者らのFNEを社会恐怖患者74名に施行し,α係数は0.92で,内的統合性は十分であった。得点分布は のごとくであり,平均得点は21点であった。 は社会恐怖とそれに関連する人格障害のFNE得点をグラフで示したものである。全般性社会恐怖は非全般性社会恐怖に比べ,統計学的有意に得点数が高かった。薬物療法と行動療法によりすべての患者で得点は減少した。

1 Ballenger JC, Burrow GD, Dupont Rl et al: Alprazolam in panic disorder and agoraphobia, results from a multicenter trial I, Efficacy in short term treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 45:413-422, 1988

2 Bandelow B, Hajak G, Holzrichter S et al: Assessing the efficacy of treatment for panic disorder and agoraphobia Ⅱ, The Panic and a Agoraphobia Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 10:73-81, 1995

3 Black DW, Wessner R, Bowers W et al: A comparison of fluvoxamine, cognitive therapy and placebo in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 50:44-50, 1993

4 Bouman TK, Emmmelkamp MG: Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia. In Van Hasselt VB, Hersen M(Eds): Sourcebook of Psychological Treatment Manuals for Adult Disorders. Plenum Press, New York, pp23-63, 1996

5 Chambless DL, Caputo GC, Jasin SE et al: The Mobility Inventory for Agoraphobia. Behav Res Ther 23:35-44, 1985

6 Charney DS, Hellinger GR: Noradrenergic function and the mechanism of action of antianxiety treatment Ⅱ. The effect of long-term imipramine treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 42:473-481, 1985

7 Davidson JR, Potts NLS, Richichi EA et al: The brief social phobia scale. J Clin Psychiatry 52(suppl 11):48-51,1991

8 Di Nardo PA, Brown TA, Barlow DH: Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-Ⅳ:Lifetime Version(ADIS-Ⅳ). Psychological Corp, San Antonio, Tex, 1994

9 Goldbrug D: Manual of the General Health Questionnaire. National Foundation for Educational Research. Windsor England, 1978(日本語版GHQ28.日本文化科学社, 東京)

10 Hamilton M: The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Brit J Med Psychol 32:50-55,1959

11 Hathway SR,McKinley JC: The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Iventry University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1942(日本語版MMPI-MAS. 三京房, 京都)

12 石川利江,佐々木和義,福井 至:社会的不安尺度FNE SADSの日本版標準化の試み.行動療法研究18:10-17,1992

13 貝谷久宣訳,牧野雄二,不安抑うつ臨床研究会編:パニック障害と広場恐怖-実践心理療法マニュアル.日本評論社,東京,2000

14 岸本陽一,寺崎正治:日本語版State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)の作成.近畿大学教養部研究紀要17:1-14, 1986

15 Liebowitz MR: Social Phobia. In Ban TA, Pichot P, Poldinger W(Eds):Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry 22. Kager, Basel, Switzerland, pp141-173,1987

16 Marks IM, Matthews AM: Brief standard self-rating for phobic patients. Behav Res Ther 17:261-267, 1979

17 宮前義和,貝谷久宣:社会恐怖・パニック障害.不安・抑うつ臨床評価に関するカンフアランス,長野1999

18 Nair NPV, Bakish D, Saxena B et al: Comparison of fluvoxamine, imipramine, and placebo in the treatment of outpatients with panic disorder. Anxiety 2:192-198, 1996

19 中里克治,水口公信:新しい不安尺度STAI日本版の作成.心身医学22:107-112. 1982

20 Ost LG: The Agoraphobia Scale, an evaluation of its reliability and validity. Behav Res Ther 28:323-329, 1990

21 大村政男:状態不安の長期的測定.日本教育心理学会第27回総会発表論文集5:394-339, 1985

22 Rapee RM, Craske MG, Barlow DH: Assessment instrument for panic disorder that includes fear of sensation-Producing acitivities, the Albany Panic Phobia Questionnaire. Anxiety 1:114-122, 1994

23 Scupi BS, Maser JD, Uhde TW: The National Institute of Mental Health Panic Questionnaire-Aninstrument for assessing clinical characteristics of Panic disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 180:566-572, 1992

24 Shear MK, Brown TA, Barlow Dh et al: Multicenter collaborative panic disorder severity scale. Am J Psychiatry 154:1571-1575, 1997

25 Sheehan DV: Sheehan Panic and A anticipatory Anxiety Scale(The Anxiety). Bantam Books, New York, 1986

26 Sheehan DV: The Anxiety Disease. Bantam Books, New York, 1986

27 Sheehan DV,Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH et al: The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.)-the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-Ⅳ and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry 59(Supp120):22-33, quiz34-57. 1998

28 清水秀美,今栄国晴:STATE-TRAIT ANXIETY INVENTORYの日本語版(大学生用)の作成.教育心理学研究29:348-353, 1981

29 Snaith RP, Baugh SJ, Clayden AD et al: The clinical anxiety scale-An instrument derived from the Hamilton Anxiety Scale. Br J Psychiatry 141:518-523, 1982(大坪天平訳)

30 Spielberger CD, Goursh R, Lushene R:Manual for the Sate -Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologist Press, Palo Alto CA,1970

31 Taylor JA:Taylor Scale of Manifest Anxiety. J Exp Psychology 42:183-188, 1951

32 Taylor CB,Sheikh J, Agras WT et al: Ambulatory heart rate changes in patients with panic attacks. Am J Psychiatry 143:478-482. 1986

33 遠山尚孝,千葉良雄,末広晃二:不安感情-特性尺度(STAI)に関する研究.日本心理学会第40会大会発表論文集.pp891-892, 1976

34 Watoson D, Friend R:Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol 133:448-457, 1969

35 Zung WWK:A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics 12:371-379, 1971

職場関連気分障害の臨床特性

「Workplace2.zip」をダウンロード

だんだんこういう統計的な話になるんだな

ーーー

病前性格としてメランコリー親和型でもなく執着気質でもないタイプが増加しているとの報告

そしてその場合の症状としてはどうかという話になるのだが

業務過重群では初期には抑うつよりも不眠、食欲不振、頭痛、パニック発作、などの適応障害型

のちに大うつ病性障害の重症ないし中等症と診断される

二段階があるという話

このあたりは難しいですね

治療しないで自然経過を見ているわけではないし

ーーー

病前性格としてメランコリー親和型でもなく執着気質でもないタイプが

初発症状としては身体化障害の系統の症状で発症すると仮説命題を立てれば

検証しやすいと思うし

そのメカニズムを議論しやすいと思う

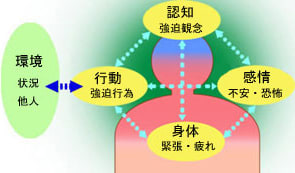

OCDやSADの治療手順 患者教育について

患者教育と呼ばれる部分

一般的情報と

その患者さんの場合の詳しいメカニズムと

分けて説明すると良いと思う

まず一般理論を解説して

では、あなたの場合はどうか、と、順番に情報を集めていく

そして何回か後に、あなたの場合のメカニズムはこうなると思いますね、いかがですか

と理解を深める

この絵を使って

個人ごとに具体的に分析するとよい

ここを工夫してくれた人がいて

まず質問をして答えを順番に埋めてゆく

そうすると自然に個人ごとの症状メカニズの図が出来上がる

そんなふうに仕組んでみた

「SADmanual.pdf」をダウンロード

この中の4ページの図は

なるべくだれにでも使えるように

やや詳細につくっています

できれば患者さんごとに省略してあげたほうが

ポイントが分かりやすくなると思います

多分、上の図のそれぞれに当てはめて

行動、認知、身体、感情、それと環境要因と対人関係などを書きこめば十分な場合も多いと思います

詳細版と簡略版を使い分けてください

ーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーーー

患者教育、家族教育の中では

薬剤についての教育も大きな部分をしめます

薬(SSRI)を効果的に利用するコツ を引用します

OCDの薬物治療でよく使われるのが、SSRI(選択的セロトニン再取り込み阻害剤)という薬です。

SSRIをはじめ抗うつ薬には、効果が出るまでに一定の時間がかかる、副作用がある、効果には個人差がある、などの特徴があります。

そのため、効果が出るまでの間に、心配になってしまう人もいるようです。

また、飲み忘れたり、自分の状態を医師にうまく伝えられないために、薬の効果が十分に得られない人もいます。

そこで、SSRIの効果をより得やすくするためのヒントを紹介しましょう。

薬は、医師の指示通りに飲むことが第一ですが、それを踏まえた上で、参考にしてください。

目次

§1 SSRIの特徴

§2 SSRIの種類

§3 副作用への対処法

§4 飲み忘れを防ぐには

§5 お薬手帳を活用する

§6 自立支援医療で、薬代も安くなる!

§1 SSRIの特徴

脳は、全体で1千数百億以上とも言われる、多くの神経細胞がつながってできています。その神経のつながっている部分(シナプス)で、神経細胞に情報を伝える役割を果たしている物質を、神経伝達物質と言います。神経伝達物質のひとつにセロトニンがあり、SSRIはセロトニンに働きかけます。

セロトニンは、一度情報を伝えると神経細胞に取り込まれてしまうのですが、SSRIは、この再取り込みを抑えて、シナプス間のセロトニンを減らさないようにします。そのような作用から、うつ病・うつ状態、強迫性障害などに効果があります。

脳には、薬などの異物が入っても、すぐに神経伝達物質の状態が変わらないようにするための、防御の仕組みが備わっています。そのため、薬で脳内のセロトニンの濃度を増やすことはできません。そこで、SSRIによってセロトニンの再取り込みを抑えて、セロトニンの量を減らさないようにします。

脳のこのような仕組みがSSRIに順応して、薬が効きだすまでに、人にもよりますが、2週間から2カ月ぐらいかかるのが普通です。その間に、薬の処方も少量から始め、徐々に増やしていきます。うつ病などの治療に比べ、強迫性障害では、SSRIの量を、通常、最大使用量まで増やさないと効果が出ないことが多いということが特徴です。

§2 SSRIの種類

SSRIのうち、OCDの治療薬として日本で認可されているものは、フルボキサミンとパロキセチンです。これは薬品の名前で、同じ薬品でも、製薬会社によって違う商品名で発売されています。患者さんが目にするのは錠剤などの商品なので、薬品名ではピンとこない方も多いと思いますので、商品名と錠剤の種類を紹介します。

薬品名 商品名 錠剤の種類

フルボキサミン デプロメール 25mg、50mg、75mg

ルボックス 25mg、50mg、75mg

パロキセチン パキシル 10mg、20mg

そのほか、セルトラリン(商品名:ジェイゾロフト)というSSRIも販売されていますが、今のところ強迫性障害の治療薬としては認可されていません。ですから、今回紹介するのは、フルボキサミンとパロキセチンについての内容です。

フルボキサミンとパロキセチンでは、服薬の回数が違います。それぞれの薬の添付文書についている強迫性障害についての内容をまとめると、次のようになっています。

薬品名 服薬の仕方

フルボキサミン 1日2回に分けて服薬する。

1日50mgから始め、1日150mgまで増量する。

パロキセチン 1日1回夕食後服薬する。

1日20mgから始め、40mgまで増やし、50mgを超えない範囲とする。

これは成人の一般的な場合で、年齢・症状に応じて、量は適宜増減されます。

§1で述べたように、強迫性障害の治療では、医師がSSRIの量を徐々に増やしながら処方していきます。1日に服薬する錠剤の数が増えてきて、飲みづらさを感じている場合は、フルボキサミンであれば50mgや75mgなど高用量の錠剤にしてもらうことで、錠剤の数が減る可能性もありますので、主治医に相談してみてください。

§3 副作用への対処法

抗うつ薬の中でもSSRIは比較的副作用の少ない薬とされていますが、薬の副作用は個人差が大きく、あまり出ない人もいれば、強く出る人もいます。セロトニンは脳だけでなく全身にある物質で、薬も血液を通じて全身に行きわたるので、副作用も体のいろいろなところに生じる可能性があります。薬の効果を最大限得るためには、副作用をうまくやり過ごす工夫も必要になってきます。

●吐き気、むかつき、食欲不振、便秘

SSRIの副作用で多いのが、吐き気、むかつき、食欲不振、便秘などの消化器に出る症状です。しかし、飲み始めの頃の吐き気などは、2週間くらいで軽くなることも多いのです。この期間は、薬の強迫症状に対する効果がまだ感じられず、副作用のようなマイナス面ばかり気になる人も多いものですが、この状態がずっと続くとは限らないということを知っておくと、しのぎやすくなると思います。

●眠気、不眠、頭がボーっとして集中できない

副作用のために日中、眠気が強くなったり、逆に夜、眠れなくなったり、頭がボーっとする、集中力が落ちるなどの症状が出ることがあります。そのため、勉強や仕事などに支障が出る人もいるかもしれません。このような場合は、医師と相談の上で、薬を飲む時間を少しずらすと、生活への支障が改善されることがあります。

1日のうち、自分が食事や睡眠をとる時間、勉強する時間、入浴や、強迫行為が出やすい時間などと、薬を飲む時間を記録して、医師に相談します。たとえば、薬を飲むとすぐ眠くなる人は、夜に飲む薬の時間を少し遅めにしたほうが、勉強をしたりするのに差し支えがなくなるでしょう。

●微熱、のどの乾き

人によっては微熱が出たり、のどの渇きなどが現れることもあります。このような体に現れる症状は、薬の副作用なのか、風邪など他の原因によるものなのか、戸惑うこともあるでしょう。こうした体調の変化があるときは、ためらわずに主治医に相談してください。

患者さんの中には、主治医に話しづらいという人もいるかもしれません。「外来の診察時間が短いから」という理由も聞きますが、「うまく言えるだろうか?」とか、「話しそびれがあってはいけない」などと意識しすぎて、話しづらくなってしまうという人もいるようです。

そんな場合は、どんな手段でもかまいませんから、なんとか「伝える」方法を考えてみてはどうでしょうか。たとえば、紙に、自分が今困っている体の症状をメモ書きして持っていき、それを医師に渡して読んでもらってもいいのです。薬物治療を成功させるには、小さなことでも遠慮しないで、主治医に話すことがとても大切です。

§4 飲み忘れを防ぐには

SSRIは、毎日飲みます。でも、うっかり飲み忘れてしまうという声もよく聞きます。飲み忘れた場合、デプロメールの患者向け医薬品ガイドには、次のように書かれています。

「決して2回分を一度に飲んではいけません。気がついた時に、できるだけ早く1回分を飲んでください。ただし、次の飲む時間が近い場合、1回とばして、次の時間に1回分を飲んでください。」

飲み忘れを防ぐために、くすり整理ケース、ピルケースなどと呼ばれる、薬を整理するための製品を使う方法もあります。薬を曜日や服薬時間によって分類して入れておく入れ物です。いろいろなタイプの製品が発売されていて、部屋に置いておくものや、携帯用のコンパクトなものもあります。

また、壁掛けの「お薬カレンダー」などと呼ばれる製品もあります。自分の生活スタイルに合わせて、使いやすいものを選ぶといいでしょう。近所の店で売っていないときは、薬局に問い合わせてもいいでしょう。ネットで検索しても買うことができます。100円ショップでも売っていることがあります。

他の薬もあって、一度に飲む錠数が多い人は、薬局に頼むと、朝の薬、夕食前の薬というように、1回の服薬分を1袋に包む分包(ぶんぽう)というサービスをしてもらえることがあります。飲み忘れないように、その袋に飲む月日を書き、飲んだらチェックするという方法もあります。

§5 お薬手帳を活用する

SSRIの服薬量は、1日に飲む錠剤の合計が何mgかで判断します。そして、その量を増減することがあるので、薬がいつから何mgになったかを知っておくと役に立ちます。

処方された薬の情報を整理するのに便利なのが「お薬手帳」です。お薬手帳は、処方箋薬局で薬を出してもらう度に、処方された薬の名前と量、日付、服薬回数、服薬方法、注意することなどを記録するもので、薬の服薬歴をまとめてわかるようにしたものです。

一般に、お薬手帳は処方箋薬局で、無料でもらえることがほとんどです。ただし、お薬手帳用の印字したシールを発行するサービスは有料の場合があります(といっても自己負担は10~20円くらい)。

特に、他の薬を飲んでいる人や、複数の医療機関にかかっている人には、薬の情報をまとめておけるので便利です。過去の服薬歴も、医師や薬剤師には重要な情報ですが、手帳を見せれば、それが正確に伝わります。SSRIには、併用することが禁止されていたり、注意が必要とされている薬もあるので、飲み合わせをチェックするためにも便利です。

お薬手帳がなくても、通常、薬局で薬の説明をプリントした紙をくれますが、それをとっておくよりも、手帳の方がコンパクトに薬の情報を整理でき、携帯しやすいことがメリットです。

§6 自立支援医療で、薬代も安くなる!

自立支援医療(⇒第40回コラム)は、公費による医療費の負担制度です。申し込むと、精神科への通院医療費や、薬代の自己負担が安くなります。毎年更新しなくてはいけないので、手続きを忘れないようにしましょう。これから申請する人は、医師の診断書が必要ですので、通っている医療機関に問い合わせてください。

SSRIは、まだジェネリック薬(後発医薬品)が発売されていません。毎日飲む薬なので、費用も案外かかります。強迫性障害は、症状のせいで働けない人も多い病気ですが、このような制度を利用することで、生活の心配が減るのなら、それに越したことはありません。安心できる体制を整えて、治療に取り組みたいものです。

ーーーーーーーーーーー

というようなあたりを教育してください

別のページでは

ーーーーーーーーーーー

OCDの治療に使われる薬

OCDの治療には、これまでさまざまな抗うつ薬や向精神薬が試されてきました。

そのなかで明らかにOCDに対する治療効果がみられたものは、SSRI(Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor:選択的セロトニン再取り込み阻害薬)というタイプの薬です。

SSRIは抗うつ薬の一つで、興奮や抑制の情報を伝達するセロトニン系の神経だけに働きかけ、神経細胞から放出されたセロトニンが、再び元の神経細胞に取り込まれてしまうのを妨げる作用があります。この結果、二つの神経細胞が接続する部分(シナプス)でのフリーセロトニンの量が増え、神経伝達の働きがよくなることで、OCDの症状を軽減させると考えられます。日本でOCDの治療薬として認められているものは、フルボキサミンとパロキセチンという薬です。

薬の飲み方

SSRIは毎日服用します。通常は、少量から服用をはじめ、通院のたびに徐々に薬の量を増やしていきます。SSRIを飲みはじめると、早い人では2~3週間で、症状が軽減するなどの反応が出てきます。しかし、多くは反応が出るまでに、もう少し時間がかかります。どのくらいの量を飲めば効果がでるのかは人によって違いますので、医師は患者さんの様子をみながら少しずつ薬の量を調整していきます。

では、どのぐらいの期間、薬を飲み続けなければいけないのでしょうか? 人によって違いますが、半年から1年ほどの治療で良好な状態となっていた患者さんでも、自己判断で薬を中断すると再び症状が現れる場合があります。したがって、少し症状が軽くなったからといって、自分の判断で勝手に薬を中断してはいけません。治療効果が安定すれば、薬の量はしだいに減らすこともできますので、最後まで主治医の指示に従って服薬を続けましょう。

ときには、SSRIの効果が得られないこともあります。その場合は、別のSSRIに薬を切り替えたり、過剰な興奮や不安を鎮める働きのある非定型抗精神病薬を少し追加したりすることがあります。

薬を安全に飲むために

●副作用

OCDの治療に使われるSSRIというタイプの薬は安全性が高く、比較的副作用が軽いのが特徴です。このように副作用も少なく長く飲み続けられる薬が登場したことで、OCDの治療は確実に向上しました。

ただし、SSRIにも多少の副作用はあります。何か気になることがあったときはすぐに主治医に報告、相談しましょう。とくに肝臓病や腎臓病、心臓病などの持病がある人や、高齢の方は副作用が出やすいので注意しましょう。 主な副作用には次のようなものがあります。

このほかにも薬を飲み始めたときや増量したときに、不安、焦燥(イライラ感)、不眠、攻撃性、衝動性、パニック発作、刺激を受けやすいなどの症状がみられることがあります。このような症状に気づいたときも、医師に報告することが大切です。

また、薬の量を急激に減らしたり中断したりした際に、一時的にめまいやしびれなどの感覚異常、睡眠障害、頭痛、悪心などがみられることがあります。このような症状は薬をやめて5日以内に現れることが多く、服用を再開すると自然になくなりますが、このような場合も「おかしいな」と感じたら主治医に相談しましょう。

●ほかの薬との飲み合わせに注意

パーキンソン病の治療に使う薬や、精神安定剤のなかには、SSRIと一緒に飲んではいけない薬があります。薬の成分が体のなかから完全になくなるまでには数週間かかりますので、OCDの治療を始める前に薬を飲んでいた人は、どのような薬を飲んでいたか、主治医に報告しましょう。

●お酒は飲まない

SSRIを服用中、アルコールを飲むと副作用が出やすくなるともいわれています。治療の間、お酒は飲まないようにしましょう。

境界パーソナリティ障害のメンタライゼーション に基づく理解

気分障害治療ガイドライン第2版

Cognitive Analytic Therapy 認知分析療法

認知分析療法

What is Cognitive Analytic Therapy (CAT)?

認知分析療法(CAT)とは?

CAT is a time-limited therapy which focuses on repeating patterns that were set up in childhood as a way of coping with emotional difficulties and deprivations .

CATは、感情的な困難と喪失を取り扱うための方法として、子ども時代に形成されて繰り返されるパターンに焦点をあてた、時間的制約のある心理療法である。

The CAT therapist and the patient, work together to recognise their maladaptive patterns and then to revise and change the patterns.

CATのセラピストと患者は、不適切なパタ-ンを認識し、修正・変更するために協力する。

CAT is particularly helpful for helping patients recognise relationship patterns that continue throughout life and are difficult to change without help.

CATは、人生を通して続いていて援助なしでは変えることが難しい、対人関係のパターンを患者に認識させるときに特に役立つ。

Features specific to CAT include the therapist writing a reformulation letter to the patient early in therapy, which is the working hypothesis for the therapy and helps promote change. The therapy is usually 16-20 sessions with the ending identified from the start.

CATに特徴的な点としては、セラピーの初期にセラピストが患者へリフォーミュレーション・レターを書くことである。

それはセラピーの作業仮説であり、変化を起こすことを助けるものである。

セラピーは通常16-20セッションであり、終了日は最初から決められている。

What sort of problems can CAT help with?

CATが援助できる問題は?

CAT is used with a wide variety of problems such as relationship difficulties, self-harm, substance misuse and eating disorders.

CATは対人関係の困難、自傷、物質の乱用、摂食障害など広範な問題を取り扱う。

Is there research evidence that it works?

有効なリサーチ・エビデンスはあるのか?

There is evidence that CAT is effective for treating general mental health problems and eating disorders. There are several research projects underway exploring the use of CAT in the treatment of a number of mental health disorders. CAT is recommended in NICE (National Institute of Cinical Excellence) guidelines for several disorders.

CATがメンタルヘルス問題一般と摂食障害の治療に対して効果があるというエビデンスがある。多くのメンタルヘルス障害の治療に対するCATの有効性を調べる研究がいくつか進行中である。CATはNICE(ナショナル・インスティテュート・オブ・クリニカル・エクセレンス)ガイドラインの中でいくつかの障害に対して推奨されている。

How long does therapy last?

セラピーの期間は?

A CAT therapy is weekly for 50-60 minute sessions. A course of therapy can be from 16-24 sessions ― this is negotiated with the therapist at the start of therapy. Between 1 and 5 follow-up sessions are offered after the end of regular therapy. Again this is negotiated with the therapist.

CATセラピーは毎週50-60分のセッションである。セラピーの1コースは16-24セッションであるーセラピーを始めるときにセラピストと話し合って決められる。

1-5回のフォローアップ・セッションが通常のセラピー終了後に提供される。これもまた、セラピストとの話し合いで決められる。

What qualifications can I expect the therapist to have?

セラピストの資質は?

A CAT therapist will have a professional qualification in a mental health related profession and a qualification from the Association of Cognitive and Analytic Therapists. This qualification enables therapist to practice CAT. Some CAT therapists will also be members of the United kingdom Council of Psychotherapists.

CATセラピストはメンタル・ヘルスに関連する分野の専門家の資格と、認知と分析の心理療法家の学会から資格を得る。

この資格があるとセラピストはCATを実践できる。英国心理療法家カウンシルの会員も兼ねているCATセラピストもいる。

What can I expect when I go for an assessment appointment?

アセスメント面接に何を期待するか?

You will be offered a 90 minute assessment appointment. This will be held in an office with two CAT therapists who will take notes and ask questions about the main problems that led you to seek help. You will also be asked about your personal history and your family history.

アセスメント面接は90分である。オフィスで二人のCATセラピストと行われる。助けが必要なあなたのメインの問題について、セラピストはメモを取りながら質問をする。

あなたの個人的な歴史(パーソナル・ヒストリー)とあなたの家族の歴史(ファミリー・ヒストリー)も尋ねられる。

At the end of the assessment you will be asked if you have any questions. If you are suitable for Cat you will be asked if you would like to start therapy. You will be informed of the approximate waiting time. You will also be sent a copy of the assessment letter yourself.

アセスメントの最後に質問があるか聞かれる。CATに向いている場合には、セラピーを始めたいかどうか聞かれる。おおよその待ち時間(期間)を知らされる。

あなた自身のアセスメント・レターのコピーも郵送される。

Once I start therapy what can I expect from the appointments?

セラピーが始まったら、面接に何を期待するか?

The appointments are weekly, in the same room. The therapist and patient sit in chairs for the sessions. The first three sessions concentrate on history taking and technique such a genograms, time lines and the CAT Psychotherapy File. A reformulation letter will be presented in the first half of therapy. This is a collaborative working hypothesis of a patients problems and the origins of these problems.

面接は毎週あり、同じ部屋で行われる。セラピストと患者は椅子に座る。最初の3回はヒストリーを聞くことに集中し、ジェノグラム、タイム・ライン、CATサイコセラピー・ファイルなどの技法が使われる。セラピーの前半にはリフォーミュレーション・レターが提出される。それは患者の問題と問題の原因に関する共同的な作業仮説である。

Maladaptive procedures and harmful relationship roles will be identified and the therapist and patient will work on recognising these patterns, as they occur both in the room with the therapist and in the patient’s life.

不適応な過程と対人関係における有害な役割が識別され、セラピストと患者はこれらのパターンの理解に努める。これらは面接室の中でセラピストとの間にも起こるし、患者の実生活の中でも起こるからである。

The therapeutic relationship between the patient and therapist is intended to be warm, non-judgemental and empathic.

Patients will be given homework tasks from time to time to encourage recognising and revising maladaptive procedures.

患者とセラピスト間の心理療法的関係は暖かく、判断を下すものではなく、同情的であることが意図されている。

患者が不適応な過程を認知し変更することを励ますために、時々、宿題が出される。

When the ending is approaching, the therapist and patient will attend to this in the sessions and goodbye letters are exchanged at the last therapy session.

These letters help the process of ending therapy and enable patients to hold on to the gains made in their CAT.

終結が近づくと、セラピストと患者は面接中にそのことに触れ、最後の面接のときにサヨナラのお手紙を交換する。

これらの手紙はセラピーを終了するプロセスを助け、患者がCATで得たものを保持し続けることを可能にする。